Written by Fernando Calderón-Figueroa, Zack Taylor, and Daniel Silver

After Donald Trump won the 2016 U.S. presidential election, cities across the country became leaders of the resistance. For many Americans, cosmopolitan cities became progressive politics’ last resort. Canadians, however, have good reason to be skeptical. After all, Toronto, Canada’s most diverse and vibrant city, has been a focal point of populist politics. Rob Ford’s election as the city’s mayor in 2010 shook Toronto’s apparently progressive political climate, and his popularity has endured following his death in 2015, helping his brother Doug become premier of Ontario in 2018.

In our recently published paper “Populism in the City: the Case of Ford Nation,” we draw on data from the Toronto Election Study, media reportage, and other sources to analyze Ford’s rhetoric and performance. We argue that Ford’s Toronto is a useful case of a distinctive variant of populist politics.

Ford’s flavour of populism is markedly different from that of recent leaders in North America and Western Europe. Their discourse combines Christian nationalism, anti-immigrant sentiments, and the moral superiority of the rural and industrial “heartland.” Ford’s rhetoric was not based on a nativist anti-immigration agenda. Some of his most fervent supporters come from racialized ethnic minorities, including Arab Muslims, South Asian Hindus, and Caribbean evangelicals. Moreover, rather than relying on an urban-rural divide, Ford’s populism was built upon the intra-metropolitan antagonism between the downtown core and the postwar inner suburbs. His coalition drew support from socially conservative suburban upper and lower classes who shared grievances against an “out-of-touch” downtown elite. For instance, Ford withdrew support to the city’s Gay Pride Parade and assailed the “war on the car” by favouring new (and much more expensive) subway lines over surface light rail projects in the suburbs.

Populism is a hot topic in social sciences. Much of this literature has examined the substantive goals of populist politicians. Building principally on the work of sociologists Rogers Brubaker and Marco Garrido, we focus instead on articulating populism’s core logic—common elements that transcend national contexts and ideological orientations.

For Brubaker, the populist repertoire is based on the opposition between “the people” and its foes. In Ford’s Toronto, those within the “ordinary people” were not defined by their ethnonational identity but by belonging to blue-collar, immigrant, and traditional middle- to upper-status families living in the suburbs. Ford often referred to this group as “the taxpayers,” and put them in opposition to the “downtown elites,” including urbanists, cyclists, university professors, “parasite” unionized workers, homosexuals, feminists, and cultural tastemakers. The geographic divide is central to Ford’s populism.

Ford’s coalition was made possible by a profound disruption: the 1997 forced amalgamation of the former two-tier Metro Toronto government with its six constituent municipalities. This brought the interests of the postwar suburbs into the centre of the new city’s politics. By the end of the century’s first decade, confidence in the municipal government was shaken by the 2009 garbage strike and rising tax burdens during an economic recession. Land-use and transportation issues became increasingly salient, pitting urban and suburban priorities against one another. In 2010, Ford campaigned against planning experts, including their consensus in favour of “Transit City,” a proposed massive expansion of surface light rail across the postwar suburbs championed by his predecessor, David Miller.

At the same time, the amalgamation created the least mediated political office in Canada, where about 1.8 million voters directly elect the mayor. Ford offered a direct channel for suburban grievances. Direct communication was key to Ford’s campaign and mayoralty. He held a weekly radio call-in show, hosted an annual Ford Fest barbecue with burgers and beer, and claimed to return every telephone call to his office personally.

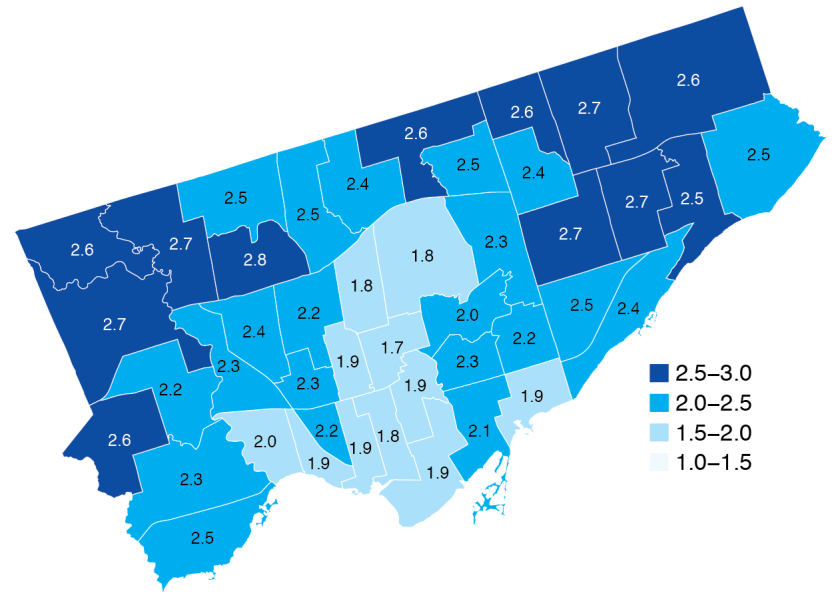

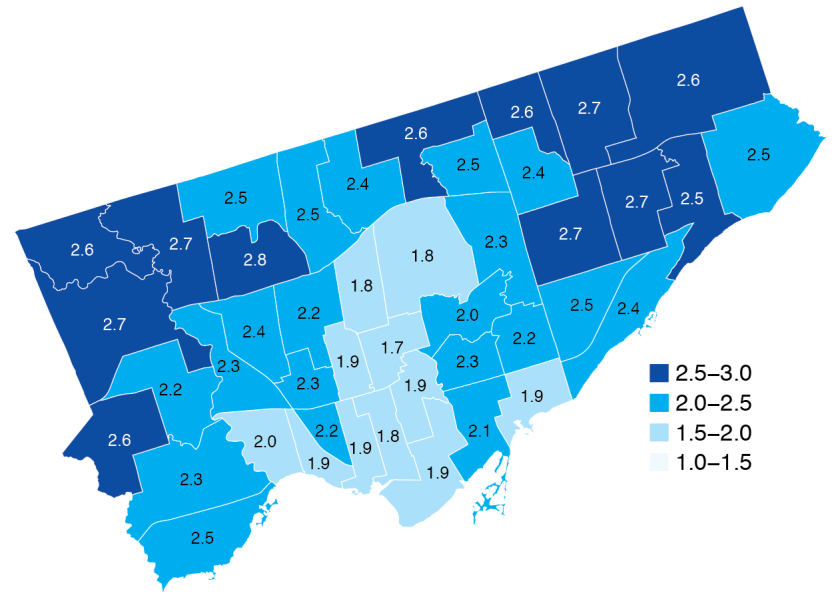

Populist leaders aim to protect the “little people” against menacing “intruders.” While in national-level populism immigrants are often deemed the outsiders, Toronto’s demographic composition and spatial divides create a different scenario. Over 50% of Toronto’s population is foreign-born and non-white. A large portion of this group lives in postwar suburbs that have faced economic stagnation or decline in recent decades. Ford’s coalition secured the support of an array of ethnic groups from these areas through his alignment with conservative values. As social and economic anxiety spread through the suburbs, the downtown core was thriving. The rising “creative class” of young professionals and artists were seen as Toronto’s “intruders.” It is not surprising, then, that the suburban areas where Ford received strongest support held feminists and the LGBTQ community in much lower regard than immigrants and racial minorities. The spatial divide of these views is clearly expressed in the maps below. Wards with darker colours indicate stronger favourability toward particular groups.

Average scores of favourability toward groups, by ward. (Source: Toronto Election Study)

Ford’s success was not simply about taking advantage of the post-amalgamation institutional environment, the crisis of confidence in the city administration, and the geography of social and economic change. It also derived from his sincere and coherent performance. The Fords, two millionaires, came to be identified with the authentic suburban ordinary people. Ford valorized qualities perceived by the elites as “low” during his interaction with supporters.

Events like Ford Fest created opportunities for people to directly connect with the populist leader and celebrate a suburban working-class way of life. Ford’s physical appearance played a critical role in this. In the words of journalist Nicholas Köhler: “When I asked one of Ford’s handlers, Nick Kouvalis, why he was content to have Ford chronicled as he ate, where another candidate might have found it unflattering, he gestured at the crowd. ‘Look at his supporters. They’re all overweight,’ he said. This method of creating identification worked; as one voter told me, ‘When you insult him, you insult us.’” Leaked videos of Ford being inebriated (just Google “Ford drunk video”) presented private behaviour coherently aligned with his public persona. At the same time, the media scandals reinforced negative attitudes towards Ford in the downtown core—this is clear in the map below. Higher scores indicate that stronger average agreement in the ward that “the media give Rob Ford a harder time than he deserves.”

Average scores for views of media treatment of Rob Ford in the 2014 Toronto election, by ward. Higher scores indicate that stronger average agreement in the ward that “the media give Rob Ford a harder time than he deserves.” (Source: Toronto Election Study)

Ford Nation survived Rob’s death in 2015. While his brother Doug lost to John Tory in the 2014 mayoral election, Doug Ford followed a similar campaign strategy, assembling a similar coalition win the 2018 provincial election. Doug Ford has remained interested in Toronto’s local politics. He cut the number of city wards in half before the 2018 mayoral election in the name of efficiency and is currently making plans for the provincial government to unilaterally take over the city’s subway system—both moves opposed by the familiar group of “downtown elites.”

Ford’s Toronto is a reminder that large cosmopolitan metropoles are not necessarily the antidote to populism; in fact, they can be its seedbed. Unevenly distributed rapid economic and demographic change across urban space may generate place-based antagonisms in other cities. In such contexts, new kinds of political mobilization may emerge—including a flavour of right-wing populism that combines multiculturalism with social conservatism in explicit rejection to cosmopolitan elites. Hopefully, this study helps us better understand these processes as they emerge.

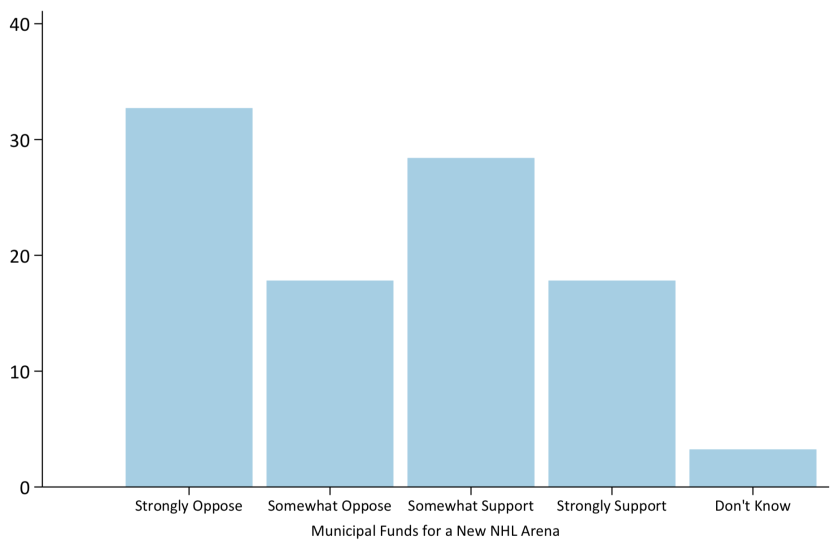

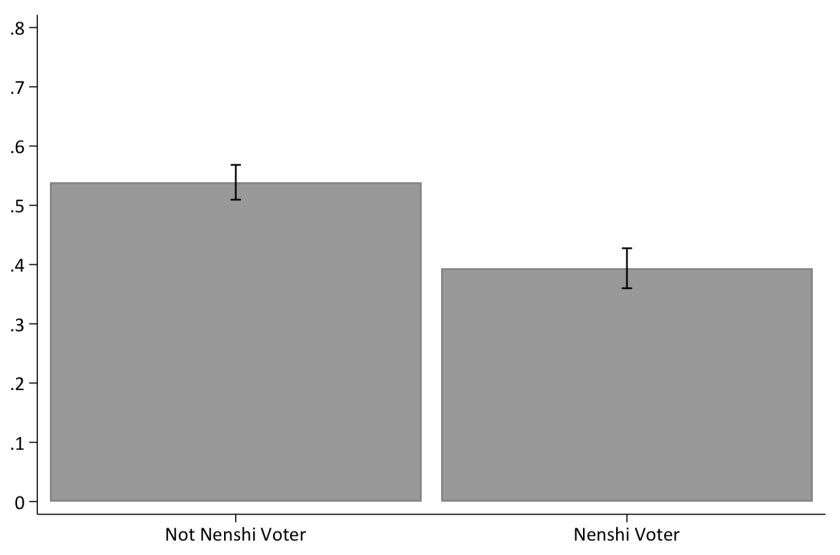

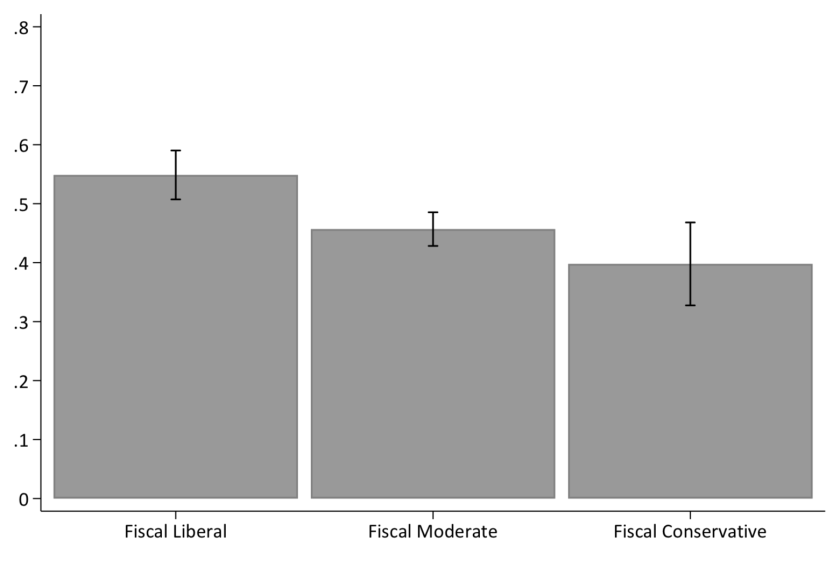

In other cases, however, we do see significant differences between the groups. Those who voted for Naheed Nenshi in 2017 are significantly less likely to support municipal funds for an NHL arena than those who voted for a different candidate in 2017 – a reflection, perhaps, of the contentious arena debates that occupied considerable attention during the 2017 mayoral campaign. Fiscal conservatives are less likely than fiscal liberals to support an NHL arena — although fiscal conservatives do not differ significantly from fiscal moderates. Civic identity (the extent to which a respondent identifies as a Calgarian) is positively related to support for the arena: in general, deeper identification with Calgary makes for higher support.

In other cases, however, we do see significant differences between the groups. Those who voted for Naheed Nenshi in 2017 are significantly less likely to support municipal funds for an NHL arena than those who voted for a different candidate in 2017 – a reflection, perhaps, of the contentious arena debates that occupied considerable attention during the 2017 mayoral campaign. Fiscal conservatives are less likely than fiscal liberals to support an NHL arena — although fiscal conservatives do not differ significantly from fiscal moderates. Civic identity (the extent to which a respondent identifies as a Calgarian) is positively related to support for the arena: in general, deeper identification with Calgary makes for higher support.

We focus on three sets of factors that may have shaped Calgarians’ feelings about the Olympic bid – these are listed along the left-hand side of the figure. The first are demographic variables like age, gender and income. The second are political variables such as provincial partisanship and support for Nenshi in the 2017 election. The final two factors are attitudes: support for spending cuts across a range of municipal services (fiscal conservatism) and strongly identifying as Calgarian (civic pride). We use regression analysis to describe the distinctive relationship between each factor and Olympic bid support.

We focus on three sets of factors that may have shaped Calgarians’ feelings about the Olympic bid – these are listed along the left-hand side of the figure. The first are demographic variables like age, gender and income. The second are political variables such as provincial partisanship and support for Nenshi in the 2017 election. The final two factors are attitudes: support for spending cuts across a range of municipal services (fiscal conservatism) and strongly identifying as Calgarian (civic pride). We use regression analysis to describe the distinctive relationship between each factor and Olympic bid support.